Commerce and the circulation of capital has been a key

concern of local politicians and planners in the Modern

Era. Technological innovations of the 19th century transformed

the Western world into industrial spheres. The railroad

and steam engine created paths along which industry and

trade centered. Chicago grew at such a trade nuclei. Urban

planning became essential to organize complex infrastructures

including transportation, communications, sewage and electricity.

Technological innovation became synonymous with the notion

of progress and modernization became the ideology of not

only industry but also the goal of urban planning. According

to Graham and Marvin in Splintering Urbanism, Western

societies regarded the standardized, orderly and unitary

city plan as the culmination of the modernist project throughout

the mid-19th century until the mid-20th century (62). During

this period of 'the modern unitary city ideal,' issues of

infrastructural and technological investment dominated urban

politics. Western cities were transformed from unplanned,

fragmented- networked systems into centralized and standardized

systems under the logic of Haussmannnisation (40-42).

These systems were meant to provide both predictable and

dependable services within urban space and in larger trade

networks. Such cities were viewed as organisms with a circulatory

system that transported goods, capital and individuals;

and respiratory systems or green space that maintained civic

and recreational health of the city (55, Burnham 80-87).

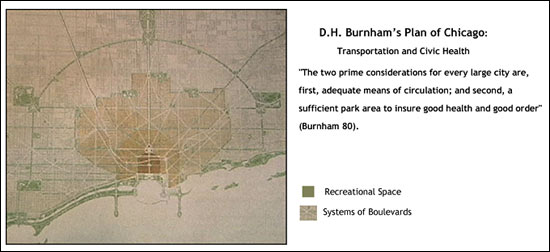

Burnham's plan of Chicago strongly emphasized an articulation

between recreational spaces and spaces that facilitate economic

flows. His plan was largely implemented. Thanks to Burnham's

plan, the entire shoreline along Lake Michigan is public

park space, and today the lake shore path serves as a transportation

highway for bike commuters and a recreational path. Burnham's

plan was largely accepted by the city because his representations

of space fit the city's idea of how Chicago had began and

would continue to develop. Burnham's ideas evolved from

a representational space to a representation of space that

the city used to design its infrastructure. This form influenced

practices of Chicago residents, and although infrastructure

of Chicago was lain in the early 1900s, space continually

is produced and reproduced through social practice and redevelopment.

"It was Haussmann's theory that the money thus spent made

a better city, and that a better city was a greater producer

of wealth" (Burnham 18).

Chicago's transportation networks facilitated a healthy

flow of capital and the city became America's main non-coastal

transportation hub (Miguel D'Escoto (CDOT), City Club of

Chicago meeting Oct. 7, 2002). His plan organized the transportation

networks into a system of radials and circuits (Burnham,

68). You can see how these circular loops spread westward

from the lake in the plan displayed above. These thoroughfares

consisted of both rail lines, a subway system and roads.

These loops were crossed by a system of diagonals designed

to save transportation time and increase circulatory efficiency.

Many diagonals 'fortunately' already existed in Chicago

before Burnham's plan (84). These radials and circuits were

lain upon a gridion system of local roadways. Boulevards

were designed mainly in residential areas so "the working

people will enjoy a maximum of fresh air and light; and

so will work with the greatest effectiveness" (86).

Beautification of the transportation infrastructure was

key to the city's civic and economic health for Burnham.

He proposed many ways to beautify the city-some were built

others remained in the space of plans. Disgusted by the

unsightly prominence railroads had taken in many other modern

cities across the world, he proposed that the freight infrastructure

be built underneath passenger infrastructure. This happened

in part by the construction of sub-ways and the 'El' or

elevated mass transit system. An aesthetic arrangement would

not only beautify the space but also enhance efficiency

of circulation. "Cleanliness and pleasing treatment of the

roadways, the embankments, the drainage channels, the fences,

yards and the stations large and small insure better service

on part of railroad employees, while the appearance of the

city is immensely improved thereby" (Burnham, 70).

Boulevards were designed mainly in residential areas so

"the working people will enjoy a maximum of fresh air and

light; and so will work with the greatest effectiveness"

(86). Burnham's intentions for Boulevards illustrate the

symbiotic relationship between the transportation and recreational

networks necessary to his vision of a healthy city The inner

transportation loop was designated for the circulation of

merchandise and goods essential to the 'elements of life'

(70). The inner circuit would also serve as the basis for

service infrastructure including water, sewers, telephone

and power (68). According to the plan, the heart of Chicago

should be surrounded by a circuit of railways intended for

both freight, subways for passengers (69). This loop would

be encased by a series of three additional roughly concentric

loops that would span outward across the cityscape. According

to Burnham, these circuits would secure a complete system

of distribution of both people and freight throughout the

city (68). His comprehensive plan's attention to circulation

and respiration is largely responsible for the economic

growth and success of Chicago in the 20th century. In the

following section I will describe the conditions of the

city streets in the late 19th century, by briefly describing

political issues, activism and representations of Chicago's

streets in maps. In subsequent sections I will describe

contemporary policy and how it developed into the Regional

Transportation Plan for 2020 in the Chicago land area. By

analyzing the history of cycling (practice), transportation

planning (representation of space) and activism (representational

space) in Chicago, I hope to make explicit such spatio-temporal

rhythms that Lefebvre describes, and the interconnectedness

of the three parts of his triad. This exploration of the

history of space should contextualize the social movement

in its relation to the 'production' of Chicago's city streets

by planners, municipal interests and the practice of everyday

life.